From Ghedh to God: The Great Moral Inversion

Western society once revered strength, order, and the disciplined pursuit of fitness in body and soul. Its earliest ideals arose from a world that understood nature as the ultimate legislator. One lived fully when one lived within the proper form assigned by nature. The Indo European peoples gave this condition a name. They called it ghedh. The word carried a rich sense of fitness and rightness. A thing or a being was ghedh when it stood in its strongest and most natural shape. It was not a flitting ideal. It expressed the hard, clean truth that every creature has a place within creation. To inhabit that place fully is moral excellence. To step outside it is ruin.

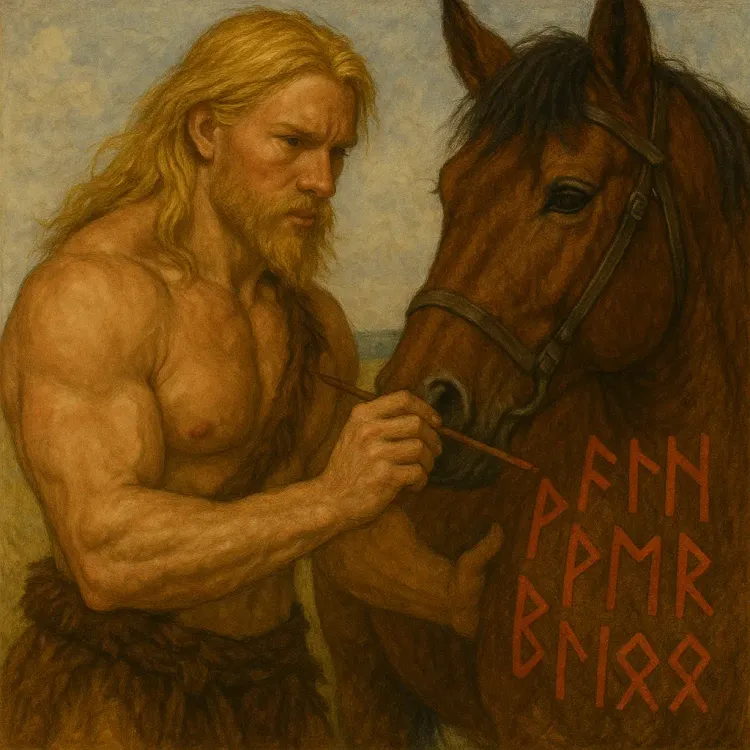

In a previous essay, we considered the image of a male lion who rules his pride. His movement with the lionesses, his guardianship of his cubs, his possession of territory, all announce that he is what he was born to be. He is ghedh when he stands amid his females and offspring as the sole adult male. It is in this setting where he will roar incessantly for all to know that he rules his territory. He is not ghedh when he wanders the savannah alone, a drifter without domain or legacy. The Indo European mind saw human life in similar terms. Strength was not a vulgar trait but a form of truth. Fitness of character, clarity of role, and the disciplined pursuit of mastery were moral virtues derived from the order of the natural world.

Pre-Christian Europe treasured this ideal. Pagan myth is a long meditation on the pursuit or loss of ghedh. The old tales do not flatter human weakness. They confront the reader with a world in which each creature thrives only when it accepts the position nature gave it. Achilles stands as the archetype of the hero who towers in strength yet nearly loses himself through misalignment. When he withdraws to his tent in rage and refuses his purpose on the battlefield, he steps outside ghedh. The tragedy of his friend’s death returns him to himself. He becomes again the fit and rightful instrument of his destiny. He returns to ghedh only when he embraces the truth that he was born for combat.

Oedipus offers the counter example. His fall does not come from moral corruption in the Christian sense. It comes from a violent breach of the natural order expressed most clearly in the tragic misdirection of his sexual desire. He seeks a queen as any rising man might, yet he chooses the one woman whom nature forbids him to touch. He kills his father on the road in a moment of rage without knowing the victim's identity, then later marries his own mother, a union that stands as the clearest possible violation of ghedh. His longing for Jocasta is not framed as perversion in the later Christian moral vocabulary. It is shown instead as catastrophic misalignment. His passion flows toward the figure who should have stood above him as origin rather than beside him as lover. The very arc of his life illustrates the pagan warning that when desire runs contrary to nature, it becomes a force of ruin. His brilliance allows him to defeat the Sphinx and liberate Thebes, yet this triumph only tightens the snare around him. He flees Corinth to escape a prophecy, but his flight becomes the mechanism by which he fulfills it. His tragedy reveals that even noble intentions cannot rescue a man once his most basic impulses have turned against the order that should guide them. The world itself responds with punishment when a man’s desire defies the form assigned by nature.

Thus the pagan vision of morality is not arbitrary. It is not built on commandments imposed from outside the world. It is a philosophy of life that springs from observation of nature. Every river, oak, mountain, and beast speaks the same wisdom. Each thrives by being what it is. The gods themselves must maintain their assigned stations or risk destruction. Even the immortals cannot escape the consequences of stepping outside their proper form. The stories of Loki, Phaethon, or Icarus show divine or semi divine figures who court doom when they abandon the limits that define their nature.

In this worldview, not everyone is destined to be a king or a great hero. Yet everyone has a natural place. Everyone can be ghedh. To be ghedh is to be the most complete and morally sound version of oneself. It is to live with satisfaction, purpose, and strength. It is to feel one’s spirit aligned with the shape carved for it by nature.

When Christian priests moved northward to evangelize the Germanic tribes, they encountered peoples whose language carried these heavy, noble concepts. They understood that the highest moral good was ghedh. To persuade these tribes that the Christian deity was worthy of worship, they reached for the strongest word the people possessed. They described the deity of the desert religion as ghedh. Out of this marriage of foreign theology with native language arose the English words good and God.

At first this caused no discord. The European mind assumed that the Christian deity must embody the virtues they already revered. They imagined that this new God must be strong. He must be the highest expression of natural fitness. He must be the cosmic warrior king whose sovereign power proves his rightness. The new religion was placed into an old framework, and the peoples of Europe assumed that the Christian deity fit within the order that nature had created.

Yet with time the ideals of the Christian faith began to replace the Indo European understanding of moral fitness. Kindness, humility, forgiveness, and equality took on the same moral weight once reserved for strength, clarity of role, and disciplined greatness. In this shift, the loss of strength signaled more than a change in taste. It marked a retreat from the very conditions that once produced fitness. Strength of body, of mind, of house, of clan. Strength had been the visible proof that a man stood in harmony with the demands of his station. When strength ceased to be honored, the pursuit of fitness itself waned. The natural world, once seen as the measure of rightness, was pushed aside. A weakened body soon mirrored a weakened spirit. The virtues of the new faith did not emerge from nature. They belonged to a spiritual realm that floated above the created world and judged it, turning the old markers of excellence into objects of suspicion.

The shift did not occur at once. For centuries Europe lived in a tension between its ancestral reverence for strength and its adopted reverence for meekness. Medieval kings still celebrated martial valor. Cathedrals still displayed lions, warriors, and pagan creatures like satyrs that adorned doors and arches. These images reminded the faithful that pre Christian Europe had never abandoned its admiration for virility and natural order. Yet doctrine pulled the moral imagination toward a new ideal. The hero of the faith was not the strong man who rose to claim his rightful place. It was the gentle sufferer who lowered himself, accepted humiliation, and forgave his enemies.

Slowly the meanings of good and God shifted. The old sense of ghedh faded. No longer did the highest good signify natural strength and rightness. Instead it signified moral softness. A man who once would have been praised for ambition, conquest, and mastery was now expected to feel guilt for these impulses. His desire to expand territory or build dominion was treated not as a natural expression of fitness but as a sin.

In the ancient Indo European world a man who sought power and strove to rule his domain lived in harmony with nature. His spirit aligned with the order that shaped him. In the Christian world that desire became something suspect. Men were told to humble themselves, to reject worldly strength, and to walk with lowered head. The traits once tied to ghedh became linked to pride. The traits once seen as signs of weakness became signs of holiness.

This inversion grew through the centuries until it formed the heart of Western moral thought. Today the modern West speaks endlessly of kindness and humility while avoiding any open praise of strength or natural fitness. Men are encouraged to suppress the instincts that once built civilizations. They are taught to distrust the desire to conquer, to protect, to win, and to reproduce. What was once noble is now framed as dangerous. What was once a mark of health is now treated as a moral failing.

The transition from ghedh to God has left the modern man disoriented. He senses the grandeur of his nature. He feels its demands for greatness. Yet he has inherited a moral vocabulary that tells him these impulses are wicked. The natural world celebrates growth, strength, and the propagation of life. The moral world of modern Western culture celebrates self denial and emotional fragility.

None of this would surprise the old pagan poets. They knew that a creature cannot thrive when it rejects its own nature. They knew that misalignment invites ruin. The tragedies of myth illustrate this truth with relentless clarity. Consider Heracles in the service of Omphale. Sent to her court as punishment for a killing committed in madness, he enters a world that inverts every part of his natural station. The greatest of heroes is stripped of his club and lion skin. He is placed in soft garments and commanded to sit among women at the loom. Omphale herself sometimes dons his lion skin and wields his club. This reversal of roles is more than humiliation. It reveals the violence done to his very nature. His strength ebbs because he stands outside the role nature carved for him. The man who cleared monsters from the world now spins wool in a foreign hall while his queen parades in the symbols of his power. When a man denies the form nature has given him, he becomes weaker and less complete. He becomes a stranger to himself.

Today the West stands in such a condition. It has taken the word that once meant strength and fitness and turned it into a symbol of softness. It has taken the natural order that once guided human flourishing and replaced it with an ethic that discourages the pursuit of greatness. Men are told to be harmless. They are told to renounce the primal energies that nature infused into them. They are told that their god embodies that soft, weak harmlessness, and so too should they.

This moral inversion extends even to the acceptance of natural joys. Sexual desire is framed as a threat rather than a creative force. The drive to compete and excel in economic or political life is tempered by guilt. Men who seek such things too greatly are considered psychopathic, power-hungry, or greedy. The will to build, to expand, to claim territory, and to secure resources for one’s kin is treated as something darkly primitive that must be overcome.

The result is a society that distrusts itself. The West has inherited a worldview that teaches people to despise their own impulses. In rejecting the ancient ideal of fitness, it has rejected the foundation of its own vitality. A civilization that teaches its men to deny their natural fitness becomes fragile. It loses the ability to defend itself. It loses the will to endure. The will to thrive.

Thus the journey from ghedh to god reveals more than a linguistic evolution. It reveals the slow transformation of an entire moral order. The ancient Indo European peoples believed that nature spoke with authority. They believed that a man who aligned his life with the shape nature had given him lived in truth. Modern Western culture believes the opposite. It encourages men to reshape themselves to match moral ideals that stand in opposition to the natural world. No civilization can endure long in such a state. For this world is still natural. A society that suppresses strength cannot survive contact with a world that still respects power. A people who believe that their natural impulses are shameful will not produce leaders capable of safeguarding their future.

The ancient world did not apologize for its strength. It understood that fitness is virtue. It understood that the will to power is not corruption but vitality. It understood that a man who claims his rightful place and fulfills the form nature assigned him is living as he was meant to live and it is beautiful to behold.

The modern world has forgotten this. Yet the truth remains beneath the surface, waiting to be uncovered. The path forward for the West requires a return to alignment with nature. It requires a renewed commitment to ghedh. Strength must again be seen as moral excellence. Fitness in body and spirit must again be revered. The desire to build, to rule, to create, and to propagate must again be honored as natural expressions of human greatness.

The ancient Indo Europeans knew that life rewards those who live in harmony with their own nature. The modern West will rediscover this truth or it will perish. The choice lies before us. We may continue to walk the path of self denial and moral inversion, or we may return to the clarity our ancestors possessed.

If Western men remember what ghedh once meant, they may yet reclaim their ancestral strength. If they refuse, they will continue their slide into weakness and self contempt. A man that despises his strongest natural form cannot endure. A man that embraces it can rise as conqueror with renewed vigor.

This is the great task of our age. To recover the meaning of strength. To return to alignment with nature. To become once more what we were meant to be. To be ghedh.