The Aristocratic Tongue

Throughout the ancient world, the Indo-European peoples defined what was right, true, and divine by reference to themselves. Their languages reveal an unbroken thread of self-affirmation: the sense that we are the measure of the cosmos, and our way of life is the natural order of things. The very words that have come down to us from their tongue—good, god, moral, virtue—still carry traces of that aristocratic self-certainty.

Good descends from the Proto-Indo-European root ghedh, meaning “fit,” “right,” or “in proper order.” The concept is not moral in the modern sense, but ontological. It speaks to whether something is aligned with nature’s pattern. A lion reigning over his pride is ghedh because he fulfills his place within the natural hierarchy; a pride without its dominant male is not ghedh, for the order has dissolved into chaos. “Good” was not about humility, kindness or pity. It meant that which stands upright in accordance with the structure of life itself.

God arises from a different Proto-Indo-European root, gheu, meaning “to pour” or “to flow.” Scholars have long insisted it is unrelated to ghedh, though the kinship in both sound and spirit is too striking to ignore. To flow rightly is to be in accord with the order of the world. The lion’s strength flows into the pride, the river flows to the sea, each thing pours itself into its appointed channel. That which flows properly is that which is good. We sense this same rhythm in ourselves when we describe being "in the zone": that effortless flow of writing, movement, or mastery where action aligns perfectly with intention and being. In this light, God names not a moral overseer but the supreme current of being, the proper flow of all things.

The early Germanic tribes understood this intuitively. Their own name for one of their greatest peoples—the Goths—is yet another echo of gheu and ghedh. As Nietzsche noted, the Goths called themselves after their own highest ideal: the people who embody what is fitting, rightful, and in-flow. Their ethic was self-referential in the most noble sense. “What is good?” they might have asked. The answer: We are good. To be Gothic was to be in tune with the natural order; to be otherwise was to be unnatural, unfit, and out of harmony. Their morality was that of self-recognition; a people holding itself as the living standard of truth.

This attitude pervaded the entire Indo-European world. Wherever they went, from the Ganges to the Rhine, they carried this same aristocratic grammar of value. To them, the good was not an abstraction but an inheritance, embodied in their blood, their customs, and their way of being.

Consider the Romans, another people who are heir to the Indo-European self-conception. The Latin moral comes from morālis, coined from mos, moris, meaning “custom, manner, way of life.” Its root lies in the Proto-Indo-European mōt, meaning “measure, standard, habitual order.” The moral, then, is that which conforms to our way, our measure. Morality was not universal law; it was fidelity to the Roman pattern of life. To act morally was to act as a Roman would.

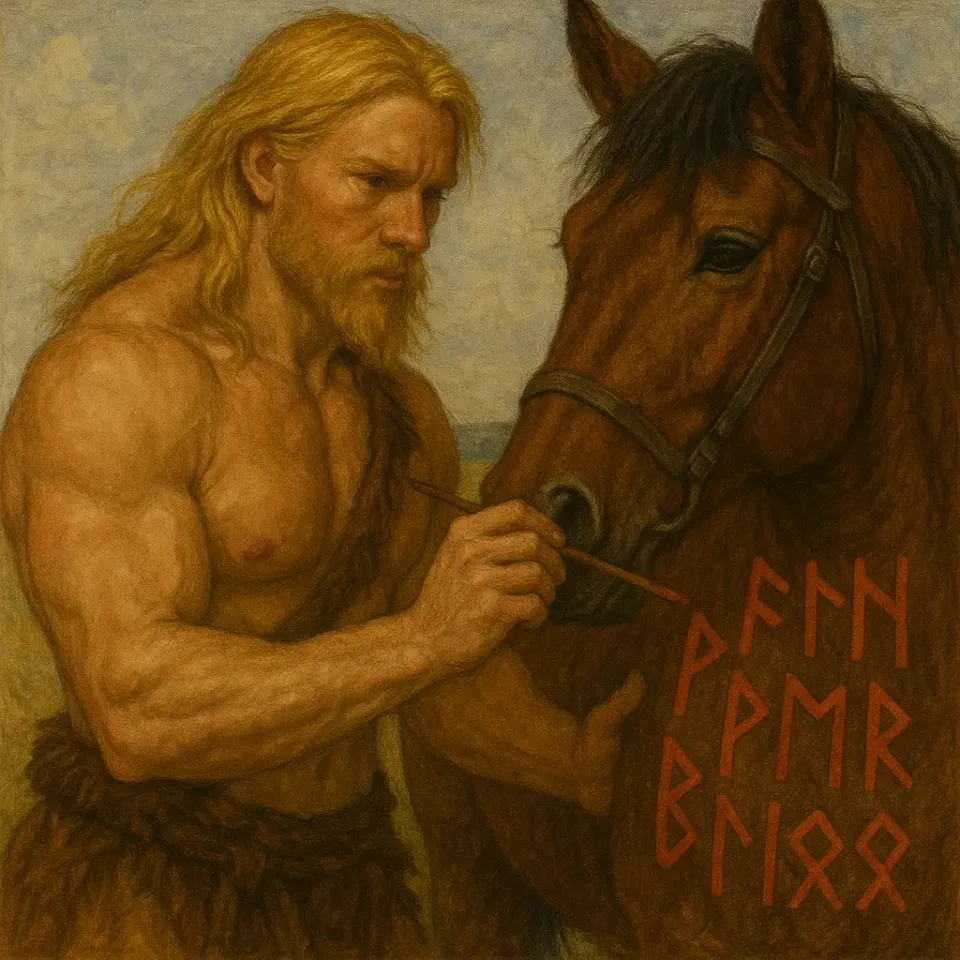

The same pattern appears in virtue. From the Proto-Indo-European wihro, “man, hero, one of worth”, came the Latin vir, meaning “man” or “warrior.” From it, virtus, meaning “manliness, excellence, courage.” Virtue meant the quality of being a man in the fullest sense: strong, capable, disciplined, master of himself and his world. For the Romans, to possess virtue was to fulfill one’s masculine essence, to embody the heroic order of nature. The Greeks called this aretē, "excellence". Both meant the same: the realization of form according to its highest function.

From India to Iceland, the pattern repeats. The Indo-European mind measured value by its own reflection. Good meant what was rightly ordered. God was the highest flow of that order. Moral meant our custom. Virtue meant our excellence. Each word encodes the same worldview: that morals, rightness, and divinity are not imposed from outside but arise from the nature of a people fulfilling its form.

Thus the Indo-European spirit is profoundly aristocratic, a philosophy of inward sovereignty and self-affirmation. It begins with the assumption that value is intrinsic, not comparative; that nobility is a birthright of form, not a concession to others. Their gods looked like them, spoke their tongue, and embodied their virtues; the divine was a mirror of the people, not an external ruler. They did not seek to imitate another race or please a distant deity. They were the standard, the measure by which order itself was known. Their myths and languages taught that to live in accordance with one’s nature was to take one’s rightful place in the hierarchy of being, the natural summit of the world’s design.

By contrast, non-Indo-European cultures, such as ancient Mesopotamia or dynastic Egypt, often built their moralities upon imitation or submission; seeking the favor of alien gods, appeasing unseen powers, or conforming to collective decrees. In these civilizations, the moral order radiated downward from celestial bureaucracy: the king or priest acted as mediator between trembling mortals and distant, impersonal divinities. Cosmic justice and universal law replaced instinct and fear replaced honor. Where the Indo-European asked, “What is fitting to my nature?” or "What is my fate?" others asked, “What is commanded of me?” One begins from within; the other from without. The first is aristocratic, rooted in strength and identity, the second servile, rooted in fear and obedience, dependent upon the external approval of deity or the universe.

The legacy of the Proto-Indo-Europeans is thus not merely linguistic but philosophical: a vision of man at his most vital, the warrior-man (vir) as the living measure of order and strength. To them, the true man was not simply male but the archetype of mastery. The one who asserts form over chaos, courage over hesitation, discipline over decay. He stands as the axis of rightness, the embodiment of virtue in its original sense of manly excellence. Their words still whisper that ancient truth: that what is good flows naturally from what is noble, and what is noble is what stands upright and unyielding in the hierarchy of being. In which hierarchy, all peoples descended from Proto‑Indo‑Europeans saw themselves at the apex: the crown of natural order and the living embodiment of natural fitness.